Warwickshire's Great Spangled Fritillary

During the summer of 1833, a young James Moreton Walhouse visited Ufton Wood near Leamington Spa in Warwickshire in order to catch butterflies for his collection.

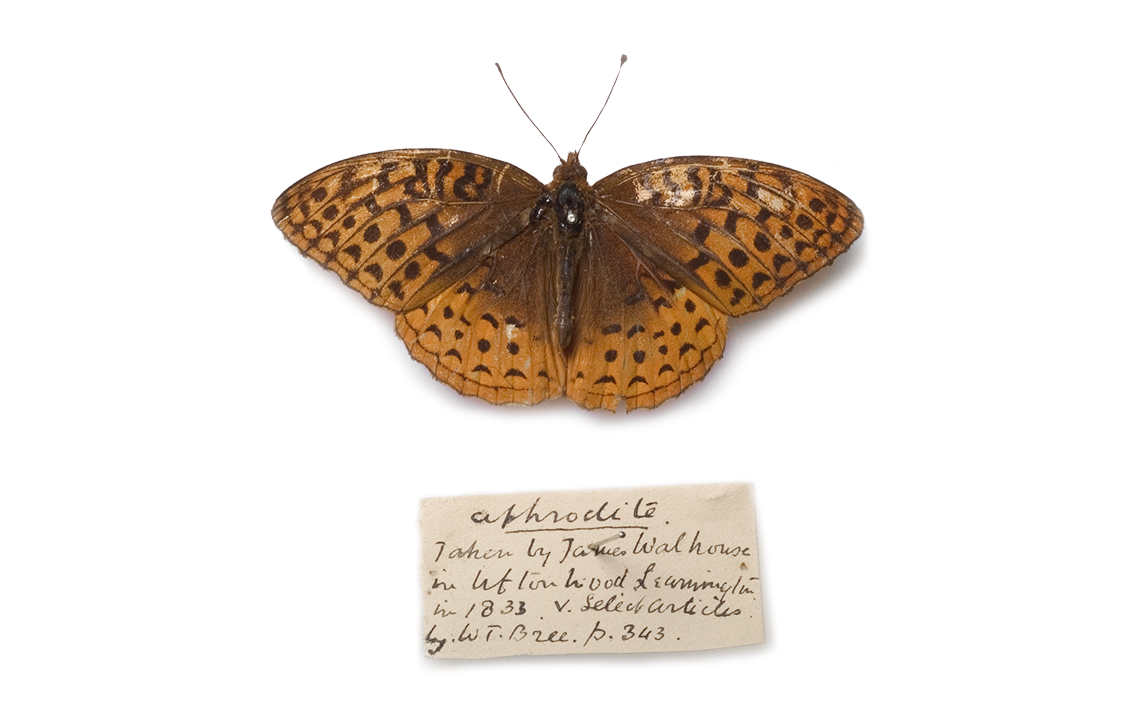

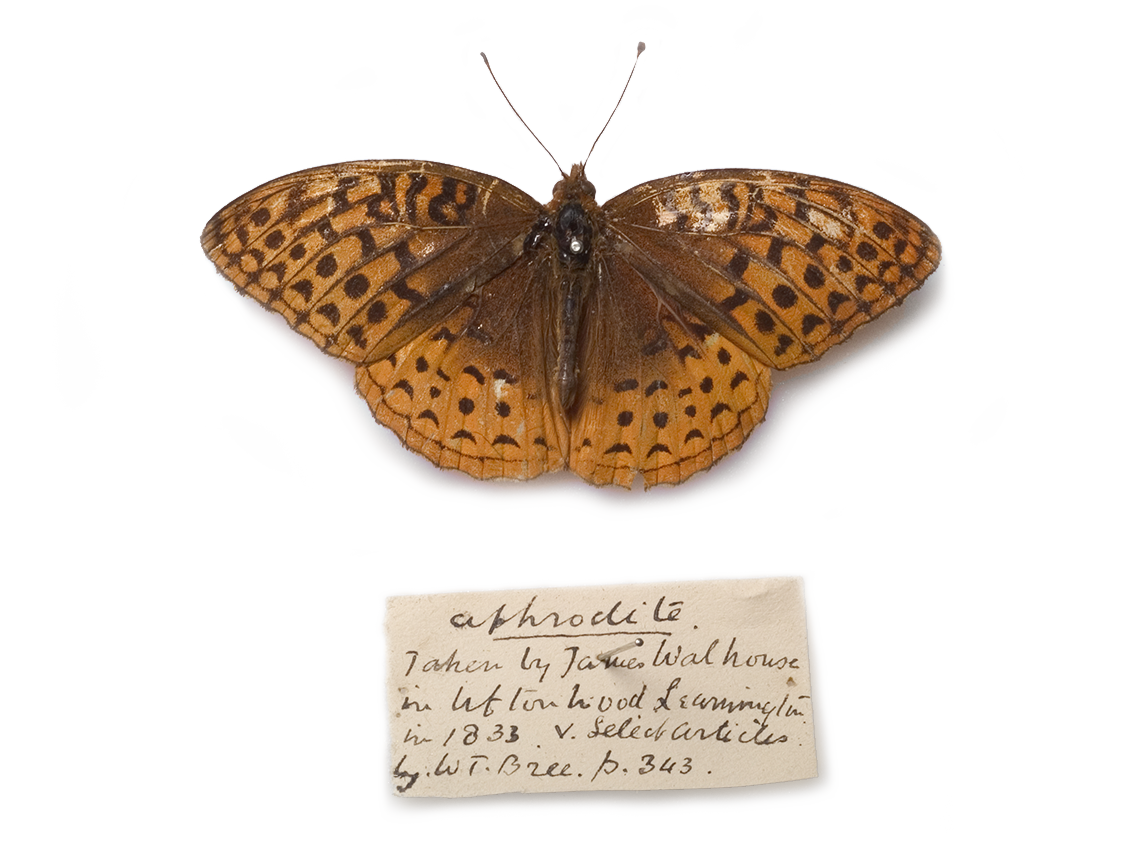

One specimen collected that day was identified as an Aphrodite Fritillary, a species not found in Europe. 170 years later, this same specimen was re-identified as a Great Spangled Fritillary after its chance re-discovery in a lock-up garage in Coventry.

When James left England and joined the army in India, he passed his butterfly collection on to his younger brother who later gave some of the collection to one of his friends named William Bree of Allesley, Warwickshire. William Bree was a keen entomologist but it was his father, the Rev. William Thomas Bree (1786–1863), vicar of All Saints' Church in Allesley who in 1840, announced in Loudon's Magazine of Natural History (see transcript below) that that an unusual butterfly originating from James Moreton Walhouse collection was Argynnis aphrodite (Bree, 1840), more commonly known as the Venus or Aphrodite Fritillary.

Bree explained how the specimen came into his possession and that it had been collected at Ufton Wood. Warwickshire in 1833. He suggested that it was unlikely that the specimen had flown across the Atlantic and put forward the hypothesis that it may have been introduced accidentally, possibly on bedding straw imported from America.

William Bree, son of Rev. W. T. Bree later became curate of All Saints' Church in Polebrook, Northamptonshire and it was here that he came into contact with Rev. F. O. Morris who visited Bree in 1852 to observe the specimen for himself.

It appears that very few people believed that this specimen still existed as it barely gets a mention after 1841 (see J. O. Westwood's book British butterflies and their transformations (Humphreys and Westwood, 1841)), except in recent publications (Howarth, 1973; Emmet and Heath, 1989). The Checklist of Lepidoptera Recorded from the British Isles (Bradley, 2000) assigned reference number 1604 to Argynnis aphrodite, based on the published reports of the specimen taken at Ufton Wood.

Re-discovery = new discovery?

In 2006, the butterfly collection of William Bree was rediscovered almost intact in a lock-up garage in Coventry. Now in the possession of Mike Mead-Briggs, amongst the many well preserved specimens was the Aphrodite Fritillary.

Photographs were posted on Peter Eeles' UK Butterflies website. Peter was subsequently contacted by David Ferguson of the Rio Grande Botanic Garden, based in Albuquerque, New Mexico who suggested that the specimen was not Argynnis aphrodite but Argynnis cybele / Speyeria cybele - The Great Spangled Fritillary!

This re-identification was later confirmed by other notable experts based in the USA, namely Paul Opler, Jonathan Pelham, Norbert Kondla and by Andrew Warren of the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity in Florida and Thomas Simonsen of the Natural History Museum, London.

Aphrodite becomes cybele

It took seven years for this specimen to be miss-identified by Bree in 1840 and almost 170 years for his mistake to be corrected. But how did the error persist for so long? It seems to be due to the illustrations published by Westwood (Humphreys and Westwood, 1841). These illustrations were based on specimens from the British Museum of Argynnis aphrodite and not on illustrations made directly from Bree's specimen. The illustrations of the British Museum specimen were reproduced several times by different authors so as far as everyone was concerned, the identification was correct. Without the rediscovery of the collection in 2006 by Mike Mead-Briggs, the mistake may never have been corrected.

This correction replaces one species of butterfly on the British list with another, Aphrodite Fritillary (Argynnis aphrodite) with the Great Spangled Fritillary (Argynnis cybele / Speyeria cybele), both native to North America. It also concludes a fascinating story and it all started at Ufton Wood in Warwickshire 191 years ago.

Acknowledgements

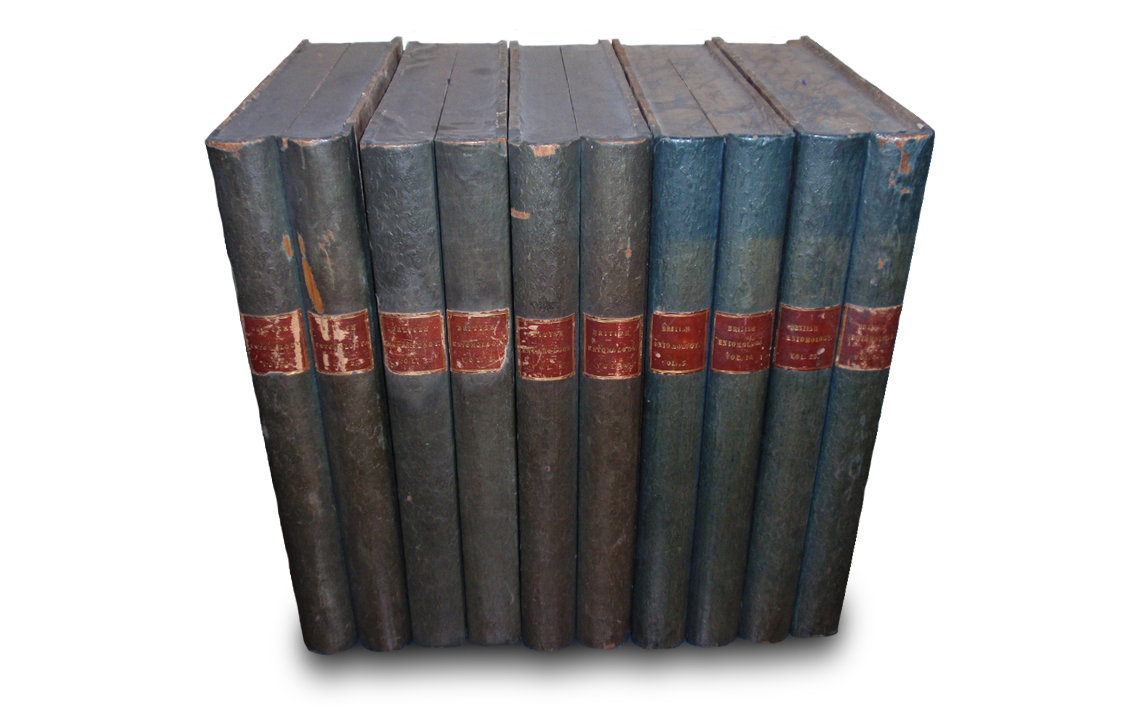

Butterfly Conservation Warwickshire would like to thank Mike Mead-Briggs who kindly supplied the photographs which accompany this text along with details of the collection and its history. We would also like to thank Peter Eeles of UK Butterflies for putting me in contact with Mike having read the original paper in the British Journal of Entomology and Natural History volume 23, part 3, 2010.

A copy of the paper published in the British Journal of Entomology and Natural History is available as a pdf on the UK Butterflies website.

References

Bradley, J. D. 2000. Checklist of Lepidoptera Recorded from the British Isles. 2nd edition. D. J. Bradley and M. J. Bradley.

Bree, W. T. 1840. Notice of the Capture of Argynnis aphrodite in Warwickshire. The Magazine of Natural History, London. Ed. E. Charlesworth. Vol. IV (New Series), pp 131-133.

Emmet, A. M. and Heath, J. (Eds.) 1989. Moths and Butterflies of Great Britain and Ireland. Vol 7, Part I. Harley Books.

Howarth, T. G. 1973. South's British Butterflies. Frederick Warne and Co. Ltd.

Humphreys, H. N. and Westwood, J. O. 1841. British Butterflies and their Transformations. William Smith, London.

Mead-Briggs, M and Eeles, P. 2010. Argynnis cybele (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) - A 'New' Record For The British Isles. British Journal of Entomology and Natural History 23: prt 3: 167-169.

Morris, F. O. 1857. A history of British butterflies. Groombridge and Sons, London.

Simonsen, T. J. 2006. Fritillary phylogeny, classification and larval hostplants: reconstructed mainly on the basis of male and female genitalic morphology (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Argynnini). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 89: 627-673.

UK Butterflies website. www.ukbutterflies.co.uk.

The Great Spangled Fritillary (Speyeria cybele / Speyeria cybele)

A North American species which is on the wing from June to September. They are often seen at nectar sources in open fields and woodland edges alongside flying with the Aphrodite Fritillary which is very similar and the species for which the Warwickshire specimen was originally confused.

More information from http://wisconsinbutterflies.org

The Venus / Aphrodite Fritillary (Argynnis aphrodite)

Also a North American species. It is on the wing from June to September.

The Aphrodite Fritillary is usually lighter in colour than the Great Spangled Fritillary, with an extra black mark near the base of the wing although this may be hard to discern in some individuals.

More information from http://wisconsinbutterflies.org

Original text from Loudon's Magazine of Natural History, 1840 pp131-133

Notice of the Capture of Argynnis Aphrodite in Warwickshire.

By The Rev. W. T. Bree, M.A.

I have the pleasure of announcing to the entomological read ere of the 'Magazine of Natural History,' the capture of an insect in this county which I believe to be hitherto entirely unheard of as a British species, — the Argynnis Aphrodite. A single example of this fine insect was taken by James Walhouse, Esq., of Leamington, in Ufton Wood, a few miles from that town, in the summer of 1833, and was kindly presented to my son, in whose possession it now is, by Moreton J. Walhouse, Esq., the brother of the captor.

In thus announcing this interesting addition to our native Fauna, I am prepared to expect that entomologists may be a little sceptical on the subject, if they do not altogether disbelieve the fact. We know but too well that dealers will, without scruple, play all sorts of tricks—frauds, I ought to say,—by attempting to pass off foreign articles for native ones, whenever it may suit their purpose. We know too, that even honest collectors are not absolutely exempt from occasional mistakes, and that, accordingly, a stray exotic does now and then creep into the British cabinet quite surreptitiously. Again we are told, and I believe told truly, that insects are not unfrequently imported, either in the egg, larva, or perfect state, with timber or other suitable merchandise. And lastly, we hear of Lepidopterous insects in the winged state, being blown over from the continent to our shores, if they have not undertaken a voluntary voyage thither. Bearing these circumstances in mind, and wishing as far as possible to anticipate objections, I deemed it right to obtain, and trust I shall be excused for stating, all the particulars I could learn relative to the subject of the present article. Let us sift the evidence, then, and see how the above objections bear upon the case before us.

And first for fraud: the specimen of Argynnis Aphrodite now before me, let it be remembered, has never been in the hands of a dealer, nor in the possession of any other person except Mr. Walhouse and his brother, from whom, as already said, my son received it. These gentlemen are men of the highest respectability, quite above all suspicion of intentional deception. I may add, too, that at the time the insect was taken, Mr. Walhouse was only just beginning to pay attention to Entomology. The immediate object of his visit to Ufton Wood was for the purpose of taking Argynnis Paphia; and so little acquainted was he at that time with our British Papiliones, that in the first instance he even doubted whether this specimen of Arg. Aphrodite were anything more than the usual sexual distinction of Argynnis Paphia. I mention this circumstance in order to show that Mr. Walhouse was not at first aware of the prize he had taken, and therefore can hardly be suspected of having been actuated by the false feeling, which might induce a dishonest person to pretend to have been the discoverer of a new British species.

But acquitting these gentlemen (as we do entirely) of anything like wilful misinformation, may we not suppose that they have fallen into a mistake, and have inadvertently allowed a foreign specimen to gain admission among their British ones? This is a fair question, and deserves consideration.— Mr. James Walhouse is now in India, and cannot conveniently be examined in the matter. On his leaving this country his collection of insects remained in the possession of his brother, Mr. Moreton Walhouse. Now I have narrowly crossexamined this gentleman as to the possibility of a foreign specimen having found its way into their collection of native insects; and he assures me, in reply, that they possessed no foreign insects whatever, till long after the time when Argynnis Aphrodite was taken. And, what is more to the purpose, Air. Moreton Walhouse informs me, that although he was not in company with his brother at the capture of Argynnis Aphrodite, he yet himself saw the specimen as soon as it was brought home, while the wings were yet limber, and before the specimen was set. Both gentlemen also were immediately aware of the great dissimilarity of the insect to any other with which they were acquainted, though they knew not what to make of it. Under these circumstances, therefore, I cannot withhold my own belief of the fact, that the individual specimen of Argynnis Aphrodite now before me, was actually taken at Ufton Wood, as above stated.

But next comes the question of importation; in answer to which it is sufficient to state that Ufton Wood is situated in a thinly-populated part of the country, remote from any port or large mercantile town, a spot, therefore, extremely unlikely to have been the depository of an insect accidentally transmitted from abroad among articles of foreign produce.

Lastly, as Argynnis Aphrodite is a native of North America, (and not, I believe, of the European continent), the notion that the specimen had, either by accident or design, made its way across the Atlantic, and settled down, in a state of good preservation, as nearly as may be in the centre of our own island, is too improbable to be seriously entertained for a moment.

I regret that Mr. Walhouse omitted to record the precise date of the capture of Argynnis Aphrodite; but as it occurred during the season when Argynnis Paphia was on the wing, it must, most probably, have been in July or August. We may conclude also that the period of flight, with both insects, is the same.

The accompanying figures (Sup. 11i. PI. x.) supersede the necessity of entering into a minute description of the insect. It is larger than Argynnis Paphia, and of the same rich fulvous colour, checkered and spotted with black, on the upper surface. The black spots and markings on the second pair of wings are niether so large nor so strongly developed as in the corresponding wings of that species, and of Aglaia and Adippe; to which latter species our insect more nearly approaches on the under surface, having the second pair of wings adorned with numerous silver spots on a buff-coloured ground, which is dark towards the base of the wings, and becomes lighter towards the lower extremities, with a marginal row of semicircular silver spots. In the grouping of our British species I should feel disposed to place Argynnis Aphrodite between Argynnis Paphia and Argynnis Adippe, possessing, as it does, some characters in common with each, while it is yet abundantly distinct from either.